by Mark L. Urken, MD Otolaryngologist – Head & Neck Surgeon, Mount Sinai Beth Israel and Medical Advisor, THANC Foundation.

The passing of Hugh Biller last month conjured up many memories of a unique individual who had a tremendous influence in my life and my career. I had the opportunity to train under him and then to serve as a member of the faculty in his Department of Otolaryngology after I returned from my fellowship.

Ultimately, I had the privilege and the honor of taking over as the Chairman of that department when he decided to step down. Dr. Biller profoundly influenced an entire generation of head and neck surgeons who were impeccably trained under his exquisite guidance and mentorship. He also left behind a wealth of creative new ideas on how best to manage cancer of the head and neck. He was one of the last head and neck surgeons who practiced virtually all aspects of head and neck surgery, from skull base to thyroid and parathyroid surgery. However, it was his love and understanding of the larynx that proved to be the organ to which he devoted the majority of his creative energy in trying to push the envelope of the discipline of partial laryngeal surgery.

I first met Dr. Biller when I was a fourth year medical student applying to residency programs. I traveled to New York from Charlottesville, Virginia to meet with Dr. Biller and to explore the opportunities for residency training at Mount Sinai Medical Center. The meeting took no more than 5 minutes and I was then advised to go to the clinic so that I could speak to the residents and get the inside scoop on what the residency program was all about. Although I do not recall the exact words that were spoken, the result of that brief interaction was sufficient to convince me to do my residency at Mount Sinai, and in particular to seek his mentorship to guide the rest of my career.

Residency training under Dr. Biller was not easy. It was an era where being on night call every other night and being on call for an entire weekend were the norm. Sleepless nights were followed by long days in the operating room. However, there was a very clear understanding of what was expected of each resident, and a clear vision of what would be achieved by enduring the challenges of that 3 year period in one’s life. Through that experience, graduating residents gained an immense amount of confidence and a remarkable ability to extrapolate from his teaching to enable them to handle virtually any problem that they might face in their career. Countless former residents used to call him for advice, not only in medicine, but also in their personal lives and every one of them reports to this day that they still hear his voice in their head when they go to the operating room, as do I.

The experience was perhaps the transformative moment in my decision to pursue a career in head & neck surgery

Perhaps one of the most memorable moments that I had with Dr. Biller came during the second year of my residency when he asked me to assist him in exploring a novel reconstructive technique for laryngeal reconstruction that he had been thinking about. Hugh Biller had a remarkable ability to visualize the head and neck in three dimensions, which aided him as a surgeon as well as an innovator. He felt that this new technique would yet again push the field of partial laryngeal surgery to a new height. I met him at a specified time in the mortuary of the old Mount Sinai Hospital where he had procured a cadaver to work out the details of this new technique. The experience of my class in gross anatomy in medical school was not a suitable preparation for the macabre scene that would await me. I ventured down into the basement of the old hospital, where the pathology lab was located, only to find a dark and dingy table with a cadaver, a set of instruments and a dimly lit swinging lamp that provided just enough illumination to carry out the procedure. The hour-long experience was perhaps the transformative moment in my decision to pursue a career in head and neck surgery. While I assisted him in fine-tuning the procedure that he had conjured up in his mind, he shared with me his thoughts on the future of head and neck cancer management and what he had envisioned to be the important role that head and neck microvascular surgery would play. From that moment, a path emerged that he mapped out for me so that I could obtain postgraduate training in microvascular free tissue transfer surgery.

Dr. Biller’s Achievements

Dr. Biller took great pride in the accomplishments of his trainees, regardless of whether they pursued a career in academia, private practice or research

Dr. Biller had spent a tremendous amount of time advancing the field of head and neck reconstruction and is largely credited with having popularized the pectoralis major and trapezius flaps, which became the mainstay of head and neck reconstruction for many years to come and are still widely used today. However, he recognized that he himself would not take the next step forward into the world of microvascular head and neck reconstruction, which was in its infancy in the latter part of the 1980s. Even though the promise of being able to transfer flaps from other parts of the body would largely supplant many of his techniques that he had advanced during his career, he was undaunted in his desire to see one of his trainees move forward into these uncharted waters. Armed with his vision for the future and a spot in one of the two fellowship training programs in this new discipline that were available to otolaryngologists, I moved forward in the next phase of my career. It is a true reflection of Hugh Biller’s greatness that he understood where the next significant advance would come from, even if he would not be the one to execute it.

Dr. Biller took great pride in the accomplishments of his trainees, regardless of whether they pursued a career in academia, private practice or research. Nothing made him happier than to acknowledge the accomplishment of one of his former residents, and he would often boast that one of his former residents was going to transform otolaryngology in a particular hospital or a particular region of the country. His influence on them was far greater than his incredible surgical technique, which included a deft handling of surgical instruments that was appreciated by all of the residents and even those medical students who chose not to pursue a career in otolaryngology. A recent conversation with an orthopedic surgical colleague, who had rotated through our service when he was a student at Mount Sinai, emphasized the significant impression that scrubbing with Dr. Biller had on his career. When I spoke with him recently, after his learning of Dr. Biller’s passing, he told me that he had spent his entire surgical career trying to perfect some of the techniques of sewing that he had witnessed during a 3 week rotation.

few will match the extent to which he moved head and neck surgery and head and neck cancer care to benefit the next generation of patients

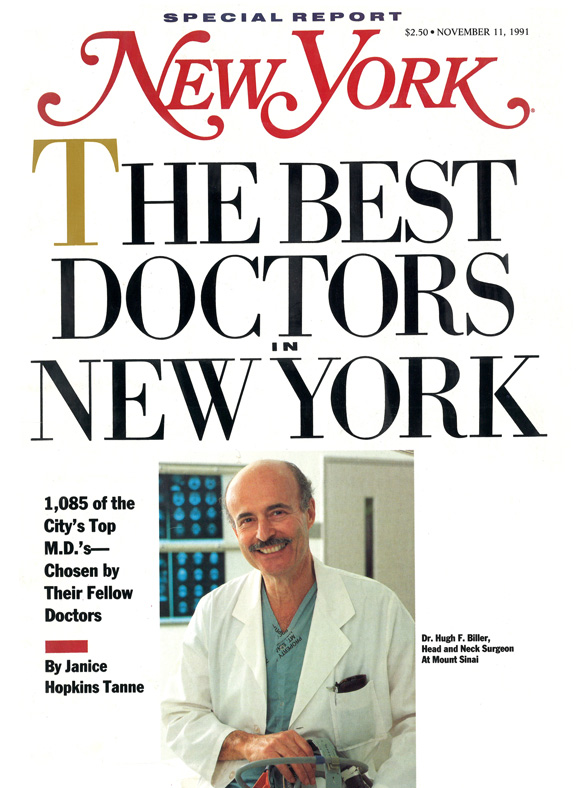

Dr. Biller’s picture appeared on the cover of the New York Magazine edition of the Best Doctors in New York. His faculty, staff and all of the residents who were in training, or had trained under him, took great pride in that recognition. However, being placed in the limelight was not something that came easily for Dr. Biller and he promptly asked that the copy of the magazine cover be taken down from the wall of the resident on call room where it had been proudly displayed. Hugh Biller had accomplished a great deal in his career, but he openly despised any semblance of what he perceived as marketing in medicine, something that has become all too prevalent in healthcare today. The only marketing that Dr. Biller recognized, and of which he approved, was the old fashioned kind that came from hard work and publishing scientific papers in peer reviewed journals, something that he did over 250 times in his academic career.

I have had the great fortune of having assumed the role of taking care of many of Dr. Biller’s patients after he retired from medicine. The impact that he had in their lives was immense. Virtually every one of those encounters, and there were many over the years, began with their desire to hear how Dr. Biller was doing. Each of those patients told stories about Dr. Biller and his positive impact on their health; on the basis of the surgical procedure he performed and equally on the way that he comforted them during a traumatic period in their lives.

Hugh Biller was truly a great doctor, surgeon, mentor and friend. He was an incredibly ethical individual who lived by those principles, and expected the very same of those that he trained and all with whom he associated. His legacy will be measured in many ways. Of those who have the good fortune to stand on his shoulders, few will match the extent to which he moved head and neck surgery and head and neck cancer care to benefit the next generation of patients afflicted with these life threatening illnesses. It is my hope that his accomplishments will not be forgotten by those who make those advances, for it was Hugh Biller, and few others who were in that stratosphere of head and neck surgeons, who paved the way for the present and future standard of care of our great specialty.