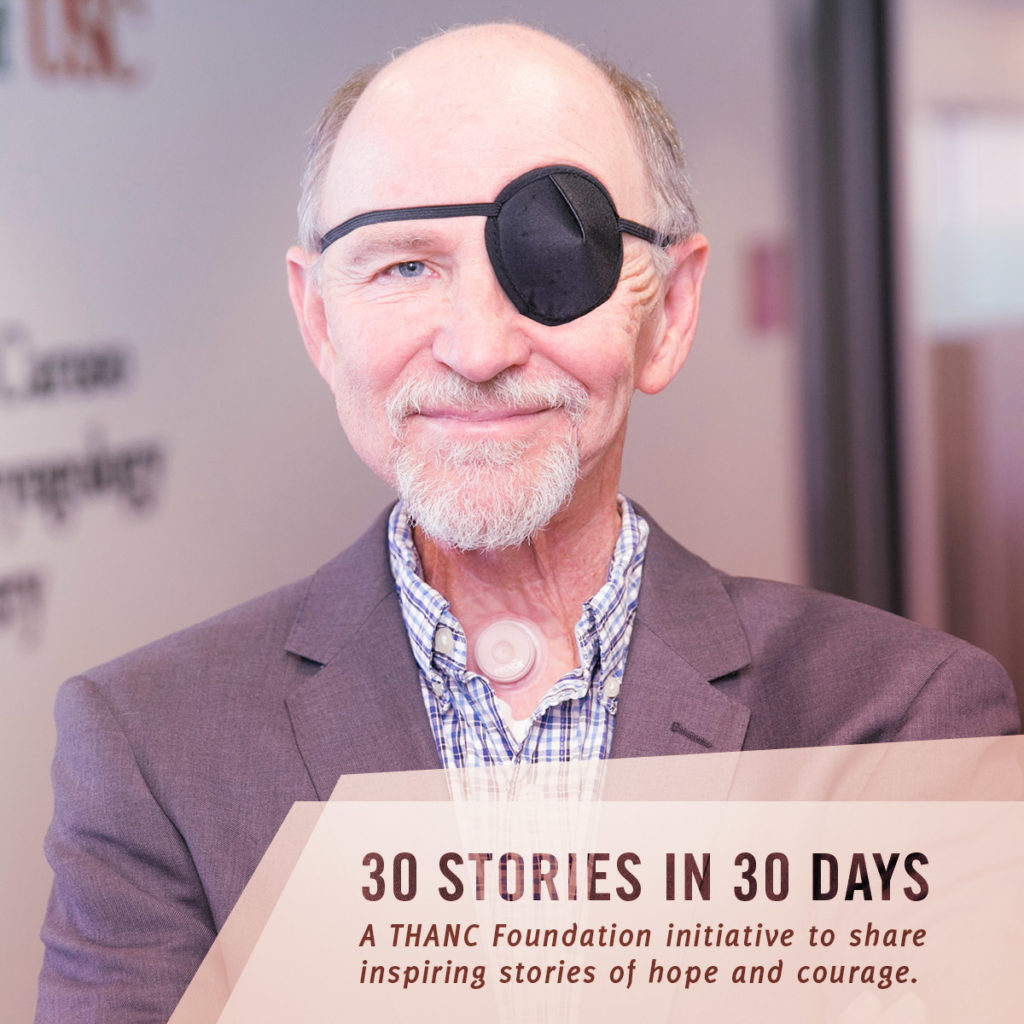

30 Stories in 30 Days

April is Oral, Head & Neck Cancer Awareness month. For the next 4 weeks, we will post stories written by oral cancer survivors, caregivers and friends for our 30 Stories in 30 Days campaign. We hope their perspectives and insight will help others along their journey.

I hadn’t uttered a word in three months. I wasn’t on an extended silent meditation retreat, nor had I taken a spiritual vow of silence. This was a forced muzzle. My speech pathologist, whom I adore, urged patience. It was running razor thin. Three months prior, I had undergone a laryngectomy, a surgery to remove my larynx. The procedure left me without a voice box, and with a hole in my neck through which I’ll breathe until I cease to do so, hopefully a long time from now. During the operation, surgeons implanted a voice prosthesis, but thus far my attempts at speech were futile.

My cancer journey started in 1997 when malignant lymph nodes were found in the right side of my neck. I was 41 years old, married, with children in elementary school, and had just started a boutique documentary production company. I had many reasons to live. But driving home after being diagnosed, the fear that I wouldn’t be around to see my children graduate from middle school enveloped me.

After undergoing a radical neck dissection, a PET scan located the primary tumor: a squamous cell cancer in my tonsil. My radiation oncologist recommended aggressive radiation treatments and was confident about my chance for survival. The radiation regimen was awful in every sense. I had burns outside my neck and inside my throat. I couldn’t keep down even the small amounts of food I was able to swallow. Over the course of seven weeks of radiation treatments and the months that followed, I lost fifty pounds. Cancer treatments had overwhelmed my body and spirit.

At my wife Frances’ urging, we ventured to the Cancer Support Community to attend support groups for newly diagnosed cancer patients and their caregivers. I felt afraid and depressed, but I didn’t think I needed help. As with most things in my life, my wife knows best. After a few weeks I still felt fearful, but no longer alone. Every person in the room with me was experiencing the same thing. At times we cried, knowing there’s healing power in shedding tears, then a few moments later we made jokes, knowing that laughter is indeed the best medicine. We mourned our physical and emotional losses, then celebrated the insights we had gained precisely because of those same losses.

Sitting in a room and talking with cancer patients helped me live more fearlessly. I was motivated by group members who, despite being exhausted by cancer treatments, still found tranquility and energy in meditation, exercise, music, yoga and other mindfulness methods. I was also inspired by those who found ways to fully experience life even while tackling a terminal diagnosis. Witnessing the grace these people exhibited led to the development of one of my pet peeves—obituaries that start with a sentence something like this: “After 3 years, Jane Smith lost her battle with cancer…” In my opinion, that sentence incorrectly defines victory and defeat. Eventually, we’re all going to die. The cause could be cancer, or it could be a variety of other illnesses, injuries, or accidents. Usually, we don’t define death as defeat in those cases.

Don’t get me wrong, fighting cancer is a battle. But I firmly believe victory should be measured not by how long we live, but by how well we live. The real battle is between despair and hope. It’s between stress and mindfulness, between isolation and community. These lessons have carried me through life, although I’ve needed occasional refresher courses.

Years later I had to have a laryngectomy to save my airway which was irreversibly damaged from the many radiation treatments. After a laryngectomy, a patient’s path to recovery is riddled with obstacles, both physical and psychological. The surgery drastically alters some of the most basic human functions – speaking, breathing, and eating. As patients struggle to adjust to their new appearance and the severe change in the way they speak, they often withdraw and avoid social interaction. A laryngectomee’s quality of life will largely be determined by his or her ability to cope with the tasks of day-to-day living, and the overall psychosocial aspects of living with a laryngectomy.

As a filmmaker and a laryngectomee, I decided I want to tell a story that will address these issues and inspire folks who’ve had a laryngectomy or are facing one. Segue is a documentary about the transition from life with a voice box, to one without. It’s told through the experiences of the members of a choir in London, made up of individuals who have had laryngectomies. This music group is an initiative of Shout at Cancer, a charity that uses singing and acting techniques to help improve voice prosthesis speech. At its heart, Segue is a stirring testimony about the human capacity for resilience, even in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Today, I’m blessed with a quality of life more resonant than before my laryngectomy, just as my doctor promised. I take walks about six days a week, totaling 90-100 miles a month. I eat well. I still get stressed, but I’ve learned how to handle it more effectively. In the past few years, I’ve proudly witnessed my son and daughter graduate from college. I’ve walked my daughter down the aisle and then become a grandparent. Twenty years ago, as I drove home from being told I have cancer, these are all experiences from which I thought I’d be absent.

I no longer hate my mechanical sounding voice. I view my disabilities arising from cancer and cancer treatments as battle scars, visible and audible signs of where I came from and what I was able to overcome. But I’m acutely aware I wouldn’t have reached secure emotional health without the love, support and encouragement of family, friends, my medical team, and the cancer survivors I am honored to know through support groups.

There’s a line in the Leonard Cohen song Anthem that speaks to finding one’s way out of whatever darkness envelopes you, and aptly describes my experience in support groups. “There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets through.” When I was at my emotional lowest, group members helped guide me to that sliver of light. In turn, the light helped illuminate my path forward. I’m forever grateful for that gift, and to the people who gave it to me.